Cultural crossroads: exploring Nairobi's natural wonders and a glimpse of Abidjan's urban greenery by Angelina S. & Andrew O.

Introduction

Nairobi, the vibrant capital city of Kenya, offers a captivating blend of natural beauty and urban sophistication. Arriving at Nairobi airport in the early hours of the morning of 10 May, 2023, I couldn’t help but notice the three-hour time difference from Abidjan and the cold temperature of 16ºC, later rising to around 18ºC throughout the day. As we drove further from the airport, a remarkable sight awaited me. I was told that the unique savannah ecosystem is a part of the Nairobi National Park, where majestic wildlife such as lions, giraffes, buffalos other wild cats thrive. The city’s streets are lined with an abundance of trees and shrubs, creating a refreshing green atmosphere. It quickly becomes apparent that Nairobi has been deliberately designed to provide its visitors with an abundance of natural attractions. This deliberate planning allows tourists to enjoy the wonders of nature while exploring the bustling heart of the capital city. This report provides an in-depth exploration of three iconic destinations in Nairobi: the Giraffe Center, Karura Forest, and the Sheldrick Wildlife Trust Elephant Orphanage. These sites offer unique histories and ecological significance, contributing to the diverse natural tapestry that defines Nairobi. The report also goes beyond Nairobi’s borders to compare and contrast it with the Banco National Park in Abidjan, shedding light on the valuable lessons each city can learn from each other.

The Giraffe Center

The Giraffe Center, located in Nairobi, is a sanctuary dedicated to the preservation and conservation of the endangered Rothschild giraffe. Founded in 1979 by the African Fund for Endangered Wildlife (AFEW), the centre has played a pivotal role in the successful breeding and reintroduction of giraffes into the wild. The history of the Giraffe Center is intertwined with that of the Rothschild giraffes, which was threatened with extinction due to habitat loss and poaching. Through educational programs and guided tours, the Centre raises awareness of giraffe conservation and offers visitors an up-close encounter with these majestic creatures. As a result of these conservation efforts, the Rothschild Giraffe population has increased significantly and is now thriving in various national parks across Kenya. This achievement is particularly noteworthy as it is the result of the successful rescue and breeding of two giraffes named Daisy and Marlon. I had the opportunity to happily feed Daisy and Eddy (Figure 1).

By maintaining a healthy population of giraffes, the centre helps to maintain the balance of this ecosystem. The giraffes, in turn, contribute to seed dispersal and vegetation management, ensuring the sustainability of the surrounding landscape. Over the years, the Giraffe Centre has educated Kenyan youth about wildlife and the environment while providing visitors with an up-close experience with giraffes. Over 2,000 teachers have been trained to empower children in nature conservation. The funds generated from the centre contribute to sustainable conservation projects in Kenya. The Giraffe Centre is a testament to the successful conservation of this magnificent species.

Figure 1 Angelina Serwaa and Andrew Orina with Eddie the Giraffe. Photo Credits Angelina Serwaa

A testament to women’s contribution to biodiversity actions – the Karura Forest

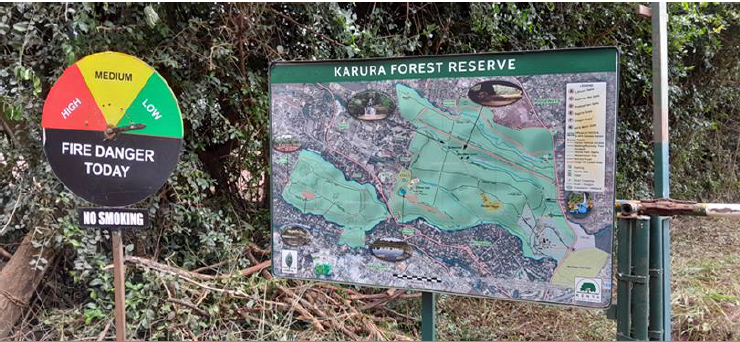

Situated on the outskirts of Nairobi, Karura Forest provides a unique setting for visitors, tourists, and residents to immerse themselves in nature without having to travel far. Covering an area of 1,000 hectares (2,500 acres) at an altitude of up to 1,712 meters, Karura Forest is classified as an upland forest, as shown on the site map (Figure 2). It serves as a retreat for nature lovers and a vibrant green lung in the heart of the city. The fascinating story of Karura Forest revolves around the inspiring tale of one woman who fought valiantly for its preservation, highlighting the remarkable contributions women have made to biodiversity conservation. The story of Karura Forest is closely linked to the activism and determination of Late Prof. Wangari Maathai, a renowned Kenyan environmentalist and Nobel laureate. In the face of urban encroachment and deforestation, she led the campaign to protect the forest from development, culminating in its gazetting as a protected area in 2005. Today, the forest is one of the largest gazetted reserves in the city and the world. Back in the 1990s, the late Professor Wangari Maathai fought tirelessly against illegal encroachment to secure the forest’s protection. Along with like-minded individuals, she co-founded the Greenbelt Movement in Kenya, which continues to make significant contributions to conservation efforts nationwide.

Nature’s contributions to human wellbeing

The few areas we explored indicated that the reserve is home to a wide range of wildlife with relatively large populations. The forest is home to over 200 bird species, numerous mammals, and a rich tapestry of plant life. Its ecosystem services include carbon sequestration, water filtration, and wildlife habitat. Karura Forest also caters to numerous cultural services. Fitness enthusiasts can jog, walk, and run along the well-maintained trails. Dedicated tennis and cycling areas provide additional opportunities for sports enthusiasts. The forest’s tranquil spots are perfect for meditation and self-reflection. Guided educational tours provide valuable learning experiences for school children. The forest also hosts social gatherings such as picnics, weddings, engagement parties, concerts, and exhibitions, all within strict regulations to ensure the preservation of the forest’s pristine environment.

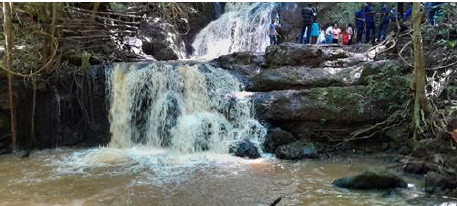

We had the opportunity to visit notable attractions within the reserve, such as the impressive 15 meter waterfall and the Lily pond near the main entrance (Figures 3 & 4). By conserving Karura Forest, Nairobi can safeguard its biodiversity and mitigate the environmental impacts of urbanization. Adjacent to the main entrance to Karura Forest are the headquarters of the International Center for Research in Agroforestry (ICRAF) and the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), emphasizing the importance of this urban green space and its link to global environmental initiatives.

Figure 2 Site map of Karura Forest reserve

Figure 3 Karura waterfall

Figure 4 Lily pond

Figure 5 the orphaned elephants in the SWT Elephant Orphanage. Photo credit Orina A.

Sheldrick Wildlife Trust (SWT) Elephant Orphanage:

We were privileged to visit the Sheldrick Wildlife Trust Elephant orphange on the outskirts of Nairobi. SWT is sanctuary for orphaned elephants (Figure 5) and rhinos. The roots of this orphan project can be traced back to the 1940s when David and Daphne Sheldrick began raising orphaned elephants in Tsavo National Park. The story of SWT is a testament to the resilience of conservation efforts in the face of adversity. Founded in 1977 by Dr. Dame Daphne Sheldrick, the organization provides critical care and rehabilitation for baby elephants and rhinos orphaned by poaching, human-wildlife conflict, or natural causes. The orphanage plays a pivotal role in the care and release of these animals back into the wild. Dr Daphne Sheldrick dedicated her life to wildlife conservation, particularly elephants, and her legacy lives on through the orphanage. Visitors to the orphanage can witness first-hand the tireless efforts of the caretakers to raise and rehabilitate these vulnerable animals. SWT has successfully hand-raised and nurtured over 244 elephants to date. These orphans undergo a three-year rehabilitation process and are eventually released back into the wild.

A tale of two urban cities: Abidjan and Nairobi:

Nairobi, an Anglophone city, is in East Africa, while Abidjan, a Francophone city is in West Africa. Despite being located in different regions of Africa, these metropolises share several common characteristics:

- Urban National Parks/green spaces: Both cities are adorned by natural park. For Abidjan, *the Banco Forest was designated as a National park in 1953, efforts led by Inspector Martineau and Governor Reste. Its original name was “Gbangbo”, an Ébrie word meaning “source of refreshing water”. It was initially created in 1926 as a Forestry research station. However, despite considerable management efforts, about 36 hectares have been lost from its original 3474 hectares due to urban encroachment and illegal logging activities in its northern areas. The park’s history is centred around the conservation of the rare monkey species. In addition, it is home to more than 1200 species of flora. The park hosts a “house of nature” museum built in 1930, an arboretum covering 12 hectares with over 700 endemic and exotic species (Figure 7), a camping area for tourists and a restaurant. The park adopts a co-management style, revenues from ecotourism are fairly shared between the local communities and park managers, NGO Vision verte and the Office Ivoirien des Parcs et Réserves, OIPR.

- Economic hubs: Both Nairobi and Abidjan serve as important economic hubs within their respective countries and regions. They are centres of commerce, finance, and trade, attracting domestic and international businesses. As key economic engines, these cities contribute significantly to their countries’ Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and employment opportunities.

- Urbanization: Both Nairobi and Abidjan have experienced rapid urbanization over the years. They have witnessed significant population growth and have faced the challenges associated with urban expansion, such as infrastructure development, housing, and transport congestion.

- Cultural diversity: Nairobi and Abidjan are cosmopolitan metropolises, characterized by their vibrant cultural diversity. They are home to different ethnic groups, languages, and religions, fostering a rich tapestry of traditions, art, music, and culinary delights. This diversity contributes to the cultural vibrancy of both cities.

- Colonial history: Nairobi and Abidjan have a shared colonial history. They were both former colonies of Europe—Kenya under British colonial rule and Côte d’Ivoire under French colonial rule. The remnants of colonial architecture, institutions, and influences can still be seen in certain parts of the cities.

- Tourism potential: Both Nairobi and Abidjan have considerable tourism potential. Nairobi is known for its wildlife safaris, national parks, and conservation efforts, while Abidjan has beautiful beaches along the Atlantic coast and cultural attractions such as St. Paul’s Cathedral.

- Infrastructure development: Both cities have been investing in infrastructure development to support their growing populations and economies. They are building modern transportat networks, improving road systems, and expanding their airport facilities to improve connectivity and facilitate economic growth.

- Challenges and opportunities: Nairobi and Abidjan face common challenges such as urban congestion, informal settlements, access to quality education and healthcare, and environmental sustainability. However, these challenges also present opportunities for innovative solutions and sustainable development strategies.

Figure 6 Maison de la nature within the Banco National Park. Photo credit: Balde S., Faye C., Dekhke E. & Gnansa E.

Figure 7 A sectional view of the arboretum – a botanical collection of over 700 species of trees within the Banco National Park. Photo credit: Balde S., Faye C., Dekhke E. & Gnansa E.

Figure 8 Education activities within the Banco National Park. Photo credit: Balde S., Faye C., Dekhke E. & Gnansa E.

While Nairobi and Abidjan have their own unique characteristics and regional contexts, these similarities provide a basis for shared experiences and potential cooperation in areas such as urban planning, economic growth, cultural exchange, and sustainable development. By learning from each other’s successes and challenges, both cities can work towards creating more inclusive, prosperous, and sustainable urban environments. Abidjan can draw inspiration from Nairobi’s success in developing and effectively managing its wildlife and ecotourism in its green spaces. Nairobi’s initiatives, such as the Giraffe Center, Karura Forest, and the Sheldrick Wildlife Trust Elephant Orphanage, serve as models for Côte d’Ivoire to promote sustainable urban development and protect its natural heritage. Côte d’Ivoire’s once thriving elephant population estimated at over 1000 individuals have declined dramatically. Today, the remaining 300 elephants live in small groups or in isolation and are highly vulnerable to poaching due to the demand for their ivory tusks. With the country currently considering the introduction of a legislation to protect the elephant population, I believe it is worth exploring possible solutions to human-wildlife conflict, such as the establishment of sanctuaries for these elephants, modelled on the successful elephant orphanage in Kenya. This will not only provide a safe haven for the elephants, but also has great potential to generate funds from tourism, offering significant opportunities for the tourism industry.

On the other hand, Nairobi can learn from Abidjan’s progress in infrastructure and urban planning. In Kenya, individuals or organisations can help protect elephants by adopting orphaned elephants. This gives people the opportunity to support animals that have lost their families and are now entirely dependent on human caregivers. Abidjan has made significant progress in improving its transport systems, waste management, and urban design. Nairobi can benefit from studying Abidjan’s experiences to address its challenges, such as traffic congestion, waste disposal, and affordable housing. Also, noteworthy, on this business trip, it is worth noting the limited availability of currency exchange services to convert West African francs CFA (FCFA) into Kenyan shillings (KES) or vice versa. In Nairobi, it can be difficult to find bureaux de change offering FCFA conversion services. Similarly, in Abidjan, it can be difficult to find places where you can exchange Kenyan shillings for FCFA. This limitation in FCFA to KES exchange options can be attributed to differences in currency markets, trading volumes, regulatory restrictions and regional trade agreements. Efforts to enhance financial connectivity and expand currency exchange services between Nairobi and Abidjan could be explored in the future. Increased collaboration between financial institutions, regulators, and governments in both cities could facilitate easier currency exchange options, thereby supporting trade, tourism, and facilitate cross-border transactions, foster economic integration and strengthen ties between these vibrant African cities.

Conclusion

Our academic stay in Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire and exploration of Nairobi, Kenya revealed a deep commitment to biodiversity and wildlife conservation. From its tranquil Karura Forest to the Giraffe Centre and Elephant Orphanage, we witnessed the tireless efforts of individuals and organisations to protect Kenya’s natural treasures. These initiatives demonstrated the co-existence of urban development and conservation, providing educational opportunities and fostering a deep connection with wildlife, a model that can be followed by other countries.

*an extract from internship report by SPIBES scholars: Balde S., Faye C., Dekhke E. & Gnansa E.